The art of making visible of visibility?

Forget conventional pictures Roland Stehlin explains, about « D’ après Nature », the Zoomby Zangger exhibition.

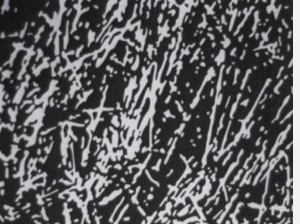

But isn’t ‘D’après Nature’ provocative? It seems to promise some still life paintings, unrecognisable landscapes. At first sight, the exhibition denies what is announced by its title. And here is the common asked question on many contemporary paintings: what does this represent? Features and colour spots are laid out in a predominance of big black and white surfaces. Abstract painting, non-figurative at first sight. Perfectly executed, strict up to asceticism. Some acid or warm colours suggest however a medium to the imagination.

But isn’t ‘D’après Nature’ provocative? It seems to promise some still life paintings, unrecognisable landscapes. At first sight, the exhibition denies what is announced by its title. And here is the common asked question on many contemporary paintings: what does this represent? Features and colour spots are laid out in a predominance of big black and white surfaces. Abstract painting, non-figurative at first sight. Perfectly executed, strict up to asceticism. Some acid or warm colours suggest however a medium to the imagination.

But we quickly get back to the first impression. When looking closer it’s all about nature, and even more, presented with a strong realism. If we do not realise that straight away, it is because the image we have about nature is conventional. In fact, the figurative painting landscape suggests a nature presentation in which the major rule is the perspective. Figurative painting shows from a distance, or at least from a right distance. Thus, the eye is able to dominate things by distinguishing them clearly. The photographer and the cineaste do the same. Enough distance is necessary for something to be recognisable. Historically, it is well known that the 19 th century photograph resulted in a mutation of painting. It’s all about reproducing the visible and fixing the ephemeral moment. The photograph is better at it than the painter. Facing this competition, something else needed to be found to be part of it. Paul Klee said it well: ‘’ the art - he says, does not reproduce the visible, it makes it visible’ what needs to be visible is not invisible religiously nor metaphysical, it’s real indeed, accessible, something that escapes for multiple reasons. An apple painted on a canvas, Picasso says, cannot be eaten. It is what makes it different from the apple on my kitchen table that I watch whenever I am hungry. Seen according to a need, I can only see what meets this need. An iron is used to perform a useful task- but if we put it on a dissection table or put some nails jutting out of its smooth surface. The surrealists have used this process: put a banal object in a rarely used environment, cancel its function, its use and that forces to look at the object itself. Like Picasso’s apple that we cannot eat. OR cancel the distance. Instead of looking at the meadow from a distance, put your nose in the grass tuft or in the muddle of a foliage. Up close, the most natural things become disconcerting. Even blades of grass become calligraphies.

It is maybe more handy to enlarge a picture and isolate the part, that is what Zoomby Zangger does to make visible what usually escapes. Therefore, this is all about nature as promised.

It is maybe more handy to enlarge a picture and isolate the part, that is what Zoomby Zangger does to make visible what usually escapes. Therefore, this is all about nature as promised.

Far from taking us out of reality, the exhibition takes us deep into it. We could call it hyper realism. However as close as we can observe it, the nature does not produce artwork to be discovered. Like any other art, imagination is there. But not in the way we believe. Once photography had imposed mutation on painting, Picasso canvasses were often seen as a pure product of the imagination. And indeed, painters have followed this way, like Salvador Dali. In an imaginary sense that would cut all links with reality, Leonardo Da Vinci was already pointing out the fact that clouds were sketching particular shapes and that figures could take shape between the cracks of an old wall. If the nature could not produce artworks, it, to a certain point, sketches them. From closer, the tree boughs draw strange signs on a sky background. Let’s get back to photography. The work is sketched. It’s all about completing the move, stressing here, shading off there, strengthening the colour by making it brighter or darker: a huge and long amount of work that tolerates no estimate. And who knows Zoomby Zangger, cannot ignore the huge amount of work at once revealed and hidden in every ‘D’après nature’ painting. A stress must be put on the word ‘d’après’ though.

Roland Stehlin

Page 3 |